This is a summary of recommendations from my book and online reading in 2025, alongside a few bonus reflections.

In 2025 I started reading or skimming around 150 books but only properly finished reading 42 books cover to cover. That’s more than I expected but fewer than I wanted. I continued neglecting canonical books that I tell myself I must read (but never get round to).1 I also read an even greater number of online essays and posts, highlighted later.

Books

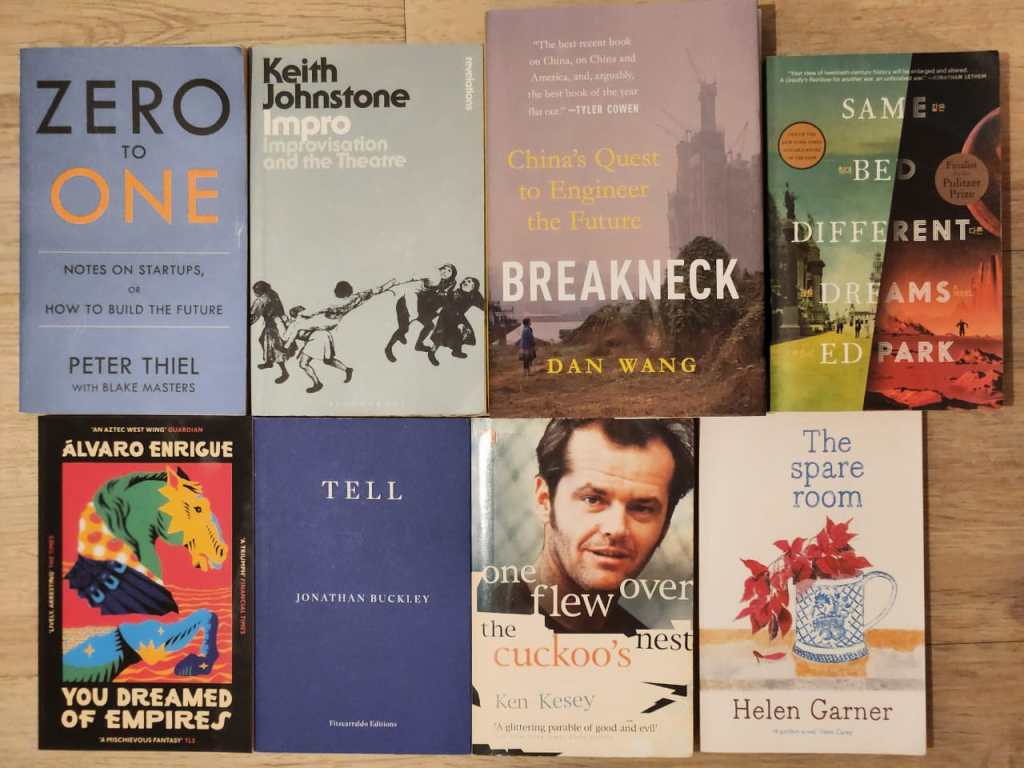

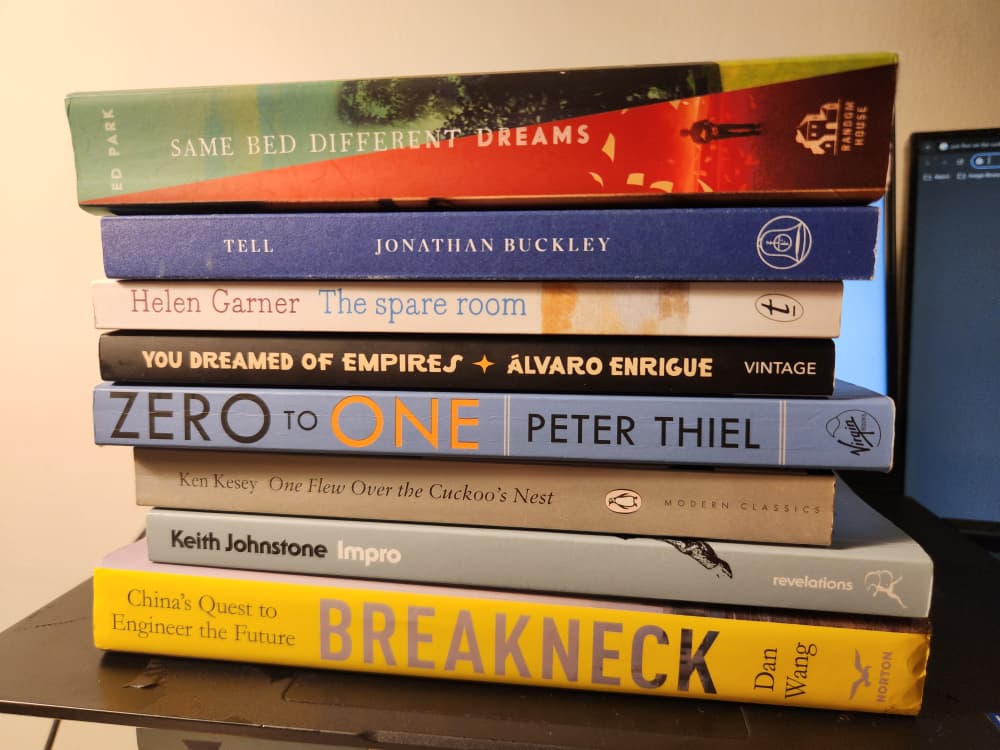

Here are 8 of the most memorable books that I read in 2025, These are not necessarily the “best” books but are those that I continue to think about months later.

And here is a book spine poem for those 8 books:

Same bed, different dreams.

Tell the spare room

you dreamed of empires.

Zero to one — flew over the cuckoo’s nest.

Impro. Breakneck.

The top 8 memorable books in order from most to least:

1. Dan Wang – Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future.

Dan Wang has had a sort of fame in certain circles as a geopolitical expert, particularly on China and tech. He is an erudite intellectual in all the best senses of the term. I’ve been a fan since reading one of his annual letters (the 2020 one published in early 2021). If you haven’t already, do read his 2025 letter here.2 A few people whom I shared it with told me that the letter is really long. It is long and chock-full of topical insights, with clear prose that is a joy to read. My only wish is that it was longer!

Breakneck has catapulted Wang into the public arena. Wang argues that today, China is an engineering state while the US is a country of lawyers. This is why China has been able to transform itself in the very recent period while the US struggles to maintain its dominance economically. However, the engineering approach has its drawbacks – notably China’s damning and damaging one child policy, as well as its response to the Covid pandemic. The social engineering state can be extremely brutal.

Here’s two podcasts where Wang appears as a guest to talk about his book, alongside many other topics: Conversations with Tyler – Dan Wang on What China and America can Learn from Each Other (Ep. 263) and Statecraft: Leninist Technocracy with Grand Opera Characteristics.

And here are some quotes as a taster:

“The greatest trick that the Communist Party ever pulled off is masquerading as leftist. While Xi Jinping and the rest of the Politburo mouth Marxist pieties, the state is enacting a right-wing agenda that Western conservatives would salivate over: administering limited welfare, erecting enormous barriers to immigration and enforcing traditional roles – where men have to be macho and women have to bear their children.”

“China is an engineering state, which can’t stop itself from building, facing off against America’s lawyerly society, which blocks everything it can.”

“Since 1980, after Deng’s reforms began, China has built an expanse of highways equal to twice the length of the US systems, a high-speed rail network twenty times more extensive than Japan’s, and almost as much solar and wind power capacity as the rest of the world put together. It’s not only the government that is fixated on production; the corporate sector is made up of overactive producers too. A rough rule of thumb is that China produces one-third to one-half of nearly any manufactured product, whether that is structural steel, container ships, solar photovoltaic panels, or anything else.”

“The United States used to be, like China, an engineering state. But in the 1960s, the priorities of elite lawyers took a sharp turn. As Americans grew alarmed by the unpleasant by-products of growth—environmental destruction, excessive highway construction, corporate interests above public interests—the focus of lawyers turned to litigation and regulation. The mission became to stop as many things as possible.”

“In the fall of 2020, I remember visiting the factory of a technology manufacturer outside of Shanghai. An executive had invited me in to tour his new production line. He was a Chinese national who had mostly worked for American companies and still traveled between the two countries. As we sipped tea in his office after the tour, we chatted about why the United States was then mired in production difficulties, unable to make much of the personal protective equipment that people wanted. “American manufacturers constantly asked themselves whether making masks and cotton swabs was part of their ‘core competence.’ Most of them decided not.” He put down his teacup and looked at me. “Chinese companies decided that making money is their core competence, therefore they go and make masks, or whatever else the market needs.”

“When we talk about technology, we should really distinguish between three things. First, technology means tools. These are the pots, pans, knives, and ovens required to prepare a dish. Second, technology means explicit instruction. These are the recipes, the blueprints, the patents that can be written down. Third and most important, technology is process knowledge. That is the proficiency gained from practical experience, which isn’t easily communicated. Ask someone who has never cooked before to do something as simple as fry an egg. Give him a beautiful kitchen and the most exquisitely detailed recipe, and he might still make a mess.”

“Zeng Zhaoqi, newly appointed party secretary of Guan County, was humiliated that it ranked last in the province for family planning. So he summoned the twenty-two most senior party officials one day in April, berating them for their failings and shouting that their measures must be more extraordinary. He demanded there be zero births in the county between May 1 to August 10. In reports now censored, residents said that every woman was forced to have an abortion, no matter how far she was into her pregnancy or whether it had been authorized. Zeng found toughs from other counties—since locals were reluctant to hurt their own—to halt births.

This incident in Guan County is known by two names: the “childless hundred days” as well as the “slaughter of the lambs,” since 1991 was the year of the sheep in the Chinese zodiac.”

“The one-child policy is one of the searing indictments of the engineering state. It represents what can go wrong when a country views members of its population as aggregates that can be manipulated rather than individuals who have desires, goals, or rights.”

“I want to invoke the classic line by professor Grant Gilmore, in a text often assigned to first-year law students: “The worse the society, the more law there will be. In hell there will be nothing but law, and due process will be meticulously observed.”

2. Peter Thiel with Blake Masters – Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future

I have the possibly disadvantageous quirk of avoiding any book/movie that receives too much hype. This is why I’ve never watched the Shawshank Redemption (#1 on IMDB for over two decades and counting), watched/read Harry Potter (fun fact, there was a whole box of hardback copies of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix in my house, days before it was released for sale, which failed to entice me), or watched/read The Da Vinci Code (this is a win, methinks). For this very same reason, I only read Zero to One this year. Boy, have I been missing out.

There exists a mythical place and time unbeknownst to the reader. If one reads voraciously enough and is blessed by the reading gods, one happens to chance upon the right book at the right time. Such was my experience reading this book. Toss aside any negative feelings about the wackiness/insanity of Thiel today. When this book came out, Thiel wasn’t obsessing over the antichrist (to my knowledge) and JD Vance had just gotten married but hadn’t started working for Thiel. This book will go down in history as one of the most important “business books” (I’m not a fan of this term) of the 21st century. Forget Blue Ocean Strategy. Trash David Epstein’s book on generalists, Range – which should have been a HBR article or listicle rather than a punishingly banal slog.

Zero to One delivers. And delivers. And then delivers yet again. Did I mention it’s also deceptively straightforward with layers of hidden depth if you stop to ponder and reflect on its applicability? Many of the ideas in this book have become mainstream, over a decade after it was published. Some haven’t.

Here are some choice quotes:

“Because globalization and technology are different modes of progress [Thiel presents a graph – technology (0 to 1) on one axis and globalisation (1 to n) on the other], it’s possible to have both, either, or neither at the same time.”

“[…] it’s hard to develop new things in big organizations, and it’s even harder to do it by yourself. Bureaucratic hierarchies move slowly, and entrenched interests shy away from risk. In the most dysfunctional organizations, signaling that work is being done becomes a better strategy for career advancement than actually doing work (if this describes your company, you should quit now).”

“”Non-monopolists exaggerate their distinction by defining their market as the intersection of various smaller markets:

British food ∩ restaurant ∩ Palo Alto

Rap star ∩ hackers ∩ sharks

Monopolists, by contrast, disguise their monopoly by framing their market as the union of several large markets:

Search engine ∪ mobile phones ∪ wearable computers ∪ self-driving cars.”

“According to Marx, people fight because they are different. The proletariat fights the bourgeoisie because they have completely different ideas and goals (generated, for Marx, by their very different material circumstances). The greater the differences, the greater the conflict.

To Shakespeare, by contrast, all combatants look more or less alike. It’s not at all clear why they should be fighting, since they have nothing to fight about. Consider the opening line from Romeo and Juliet: “Two households, both alike in dignity.” The two houses are alike, yet they hate each other. They grow even more similar as the feud escalates. Eventually, they lose sight of why they started fighting in the first place.

In the world of business, at least, Shakespeare proves the superior guide. Inside a firm, people become obsessed with their competitors for career advancement. Then the firms themselves become obsessed with their competitors in the marketplace. Amid all the human drama, people lose sight of what matters and focus on their rivals instead.”

“As a good rule of thumb, proprietary technology must be at least 10 times better than its closest substitute in some important dimension to lead to a real monopolistic advantage. Anything less than an order of magnitude better will probably be perceived as a marginal improvement and will be hard to sell, especially in an already crowded market.”

“Having abandoned the search for technological secrets, HP obsessed over gossip. As a result, by late 2012 HP was worth just $23 billion—not much more than it was worth in 1990, adjusting for inflation.

“As a general rule, everyone you involve with your company should be involved full-time. Sometimes you’ll have to break this rule; it usually makes sense to hire outside lawyers and accountants, for example. However, anyone who doesn’t own stock options or draw a regular salary from your company is fundamentally misaligned. At the margin, they’ll be biased to claim value in the near term, not help you create more in the future. That’s why hiring consultants doesn’t work. Part-time employees don’t work. Even working remotely should be avoided, because misalignment can creep in whenever colleagues aren’t together full-time, in the same place, every day. If you’re deciding whether to bring someone on board, the decision is binary. Ken Kesey was right: you’re either on the bus or off the bus.”

“Why work with a group of people who don’t even like each other? Many seem to think it’s a sacrifice necessary for making money. But taking a merely professional view of the workplace, in which free agents check in and out on a transactional basis, is worse than cold: it’s not even rational. Since time is your most valuable asset, it’s odd to spend it working with people who don’t envision any long-term future together. If you can’t count durable relationships among the fruits of your time at work, you haven’t invested your time well—even in purely financial terms.”

“From the outside, everyone in your company should be different in the same way. […] On the inside, every individual should be sharply distinguished by her work.”

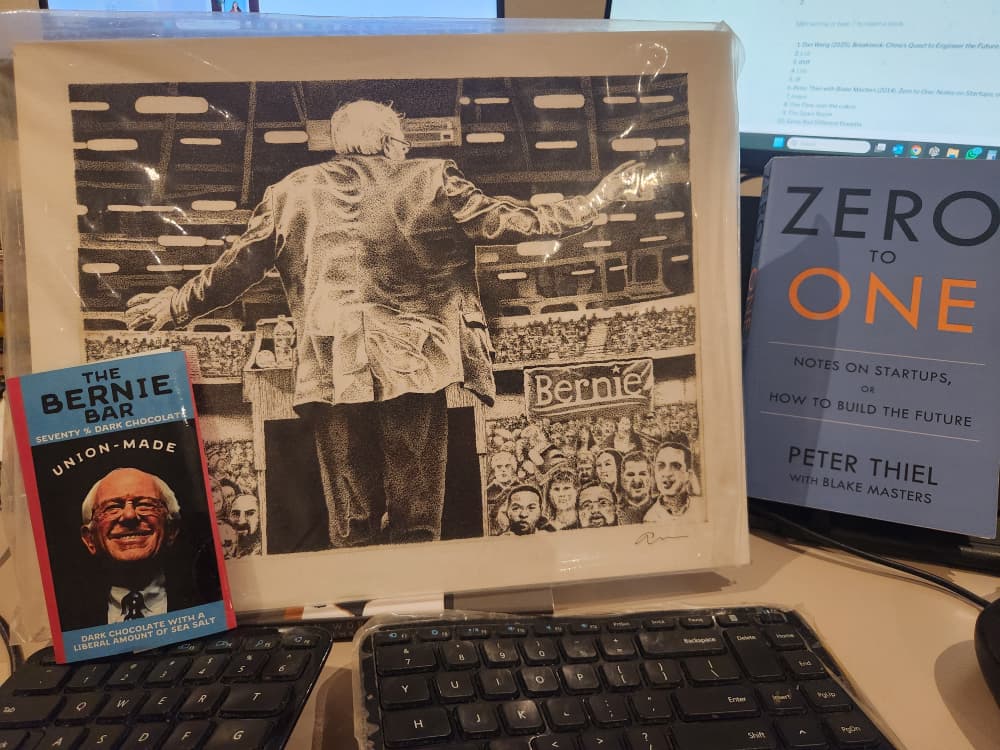

If all this makes you nauseous, I understand. You rail against tech bros and The Silicon Valley Canon. You are an AOC fanboy and love “Feeling the Bern” with Sanders (Bernie, not the Colonel, I might have to clarify for some readers). At the very least, you can venture into this book as a sociological excursion into the tech/startup bro milieu. And/or take up a spiritual challenge and accept that two opposites can be true at the same time. Here’s a photo of my desk right now as I type this – my copy of Zero to One next to an artwork of Bernie and a chocolate bar (dark chocolate with a liberal amount of sea salt!) I picked up in Burlington, Vermont several years back.

3. Keith Johnstone – Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre

This classic from 1971 was written as a guide to improvisation in the context of the theatre stage. It was duly embraced by thespians but somehow along the way, became a cult classic among techies. See for example this post by Venkatesh Rao (Ribbonfarm) who reviews it better than I could hope to.

After years of Impro being on my radar, I finally finished it in 2025. Much of it is practical advice, though is it not somewhat sociopathic, or at the very least manipulative? Well, I reckon if books on body language and posturing are accepted and promoted at the workplace, then why not Impro? The chapter on Status was the most immediately relevant section – on how to play high/low status. The chapter on Narrative Skills gave me one of the most valuable pieces of writing advice which has slowly helped me come unstuck: “(1) interrupt a routine; (2) keep the action onstage—don’t get diverted on to an action that has happened elsewhere, or at some other time; (3) don’t cancel the story.”

And here’s some quotes:

“My feeling is that a good teacher can get results using any method, and that a bad teacher can wreck any method.”

“Suddenly we understood that every inflection and movement implies a status, and that no action is due to chance, or really ‘motiveless’. It was hysterically funny, but at the same time very alarming. All our secret manoeuvrings were exposed. If someone asked a question we didn’t bother to answer it, we concentrated on why it had been asked. No one could make an ‘innocuous’ remark without everyone instantly grasping what lay behind it. Normally we are ‘forbidden’ to see status transactions except when there’s a conflict. In reality status transactions continue all the time. In the park we’ll notice the ducks squabbling, but not how carefully they keep their distances when they are not.”

“Status is a confusing term unless it’s understood as something one does. You may be low in social status, but play high, and vice versa.

For example:

TRAMP: ’Ere! Where are you going?

DUCHESS: I’m sorry, I didn’t quite catch . . .

TRAMP: Are you deaf as well as blind?

Audiences enjoy a contrast between the status played and the social status. We always like it when a tramp is mistaken for the boss, or the boss for a tramp. Hence plays like The Inspector General. Chaplin liked to play the person at the bottom of the hierarchy and then lower everyone.”

“If you experiment with master-servant scenes you eventually realise that the servant could have a servant, and the master could have a master, and that actors could be instantly assembled into pecking orders by just numbering them. You can then improvise very complicated group scenes on the spur of the moment.”

“We all know instinctively what ‘mad’ thought is: mad thoughts are those which other people find unacceptable, and train us not to talk about, but which we go to the theatre to see expressed.”

“In some cultures dead people are reincarnated as Masks—the back of the skull is sliced off, a stick rammed in from ear to ear, and someone dances, gripping the stick with his teeth. It’s difficult to imagine the intensity of that experience.”

“”Many ways of entering trance involve interfering with verbalisation. Repetitive singing or chanting are effective, or holding the mind on to single words; such techniques are often thought of as ‘Oriental’, but they’re universal.”

“Crowds are trance-inducing because the anonymity imposed by the crowd absolves you of the need to maintain your identity.”

4. Ken Kesey – One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest

Published in 1962, I first read it in the mid-2000s, before I went to university, while also watching the movie starring Jack Nicholson shortly after. My copy has Jack Nicholson on the cover; the movie has some differences to the book, but the overall plot and themes are largely intact. I reread it in 2025 – it still holds up more than 60 years later. I love it.

Looking back over the past two decades, this book has subconsciously influenced my perspective on life in two ways. I’m probably revealing too much here but: (1) Questioning authority, not accepting it blindly, and pushing back (in subtle ways) if necessary; and (2) Valuing the luxury of being “free”, in the libre not gratis sense. I’m still too young and foolish to know if these perspectives are to my benefit or detriment.

In this novel, Nurse Ratched, the embodiment of authority, rules the psychiatric ward of a hospital with an iron fist (and iron heart?). Chief Bromden, our narrator is a half-Native American who pretends to be a deafmute. One fine day, in waltzes Randle McMurphy, a genuine shit-stirrer who rebels against Nurse Ratched and everything she represents. The patients slowly begin to revere McMurphy as a trickster messiah. Well, we know what happened to Jesus. “It’s the truth even if it didn’t happen.”

Parts of the book are genuinely moving. We find ourselves rooting for the motley crew of patients, celebrating their victories however small and temporary. Blessed indeed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.

Trigger warning: small sections of the book might not be considered “woke” by today’s standards. But the book shouldn’t be inappropriately judged with this lens, as it is an artifact of its time, the Swinging Sixties. Let them who be without sin, cast the first stone.

Now that I think about it, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest is kinda like Dead Poets’ Society (the 1989 movie starring Robin Williams), but set in a psychiatric hospital ward. “He who marches out of step hears another drum.”

5. Helen Garner – The Spare Room

In 2025, I was in Australia for the third time, for an Oasis concert! Before that, I had visited twice in 2018 (first for an old and very close friend’s wedding and the second for a family holiday). Now here’s a side story I’ve not told before. My (late) father hated travelling. Until I finished secondary school, the furthest from Penang I had ever ventured in my life was three short jaunts to KL. Holiday travels were confined to Alor Setar, where we would stay with close family friends and their extended family. My parents used to live and work in that town, before I was born. Some of these Alor Setar folks then migrated to Melbourne. Every time they came back for a visit or on telephone calls, they would ask my father when would he be coming over to visit them. He would never go, of course. Some years later one of their family members dies from cancer. In 2018, he finally goes to Australia to fulfil a promise to “visit”, alas to a grave.

Where is this going? I’m not quite sure, but all of this is a roundabout way of saying that in my mind, since then, Australia has been associated with death and the departed. It’s also a country where Malaysian dreams go to die. But that’s a diversion for another time. Which brings us to The Spare Room by Helen Garner. Autofiction (autobiographical fiction) seems to be the rage these days. Dear Reader, was the little tale that I just shared actually a tall one?3

I wanted to read more Australian writing and Helen Garner is one of the leading writers of Naarm (Melbourne). This is a relatively short and punchy novel about Helen who hosts her friend Nicola who has advanced cancer and is probably going to die. Nicola lives in Sydney but has travelled down to Melbourne to see what can generously be described as an alternative medical practitioner. When Death seems to be at the door, a gamut of emotions, both positive and negative run through our minds and the minds of the people around us. This is a believable story, both sentimental and unsentimental. Two opposites can be true at once, remember?

I loved the ending, no spoilers from me. Besides this 2008 novel, I read a bit of the start of Monkey Grip, the 1977 novel that won Garner some fame and notoriety. From the bits that I read, they are two very different novels with very different styles – unlike say Ishiguro or Wodehouse who have a consistent unique voice. I prefer the version of Garner’s writing here – punchy and direct.

6. Ed Park – Same Bed Different Dreams

Ed Park is a talented and skilled writer, without a doubt. In Same Bed Different Dreams he tries his very best to be too clever. Sometimes it work and it pays off, the reader is thrilled. Sometimes, it falls flat. Sometimes, the reader is confused whether something was intentional or not. For example, I wasn’t sure if I had wrongly imagined that the names of some of the characters were intended puns and cultural references. But I did enjoy the entire wacky ride.

I described this novel to a friend as David Mitchell meets Philip K Dick, but make it Korean-American. Perhaps it is better to go into this novel blind. All you need to know is that there are multiple narratives that take turns and that much of it is alternate history and sci-fi, so suspend your disbelief. Perhaps readers well-versed in Korean history might get an even bigger kick out of this book.

7. Jonathan Buckley – Tell

I did consider naming this post “From Thiel to Tell”, but decided against it. This was my first encounter with Jonathan Buckley. I came across a review describing Buckley’s writing as Cuskian (as in the Rachel Cusk sense). Not having read any Cusk, I then went to procure her Outline Trilogy. I have yet to read any Cusk. But reading Tell made be go and buy more of Buckley’s work – I read Telescope and One Boat, both listed below.

The premise of this novel is that the protagonist, a wealthy businessman has disappeared and is possibly dead. Everything we learn in this novel is through the filter of what his gardener tells an interviewer. We see the thoughts and actions of all the characters through the gardener’s eyes. Truth or lie, we only have the gardener’s word to judge.

This book currently has a low 3.27 rating on Goodreads. I can see why people would hate this book. I enjoyed it, but I rated it only four out of five stars. However, I continued to think about and recommend this novel, even weeks later.

8. Alvaro Enrigue; Natasha Wimmer (translator) – You Dreamed of Empires

A novel about the conquistadors meeting the Aztecs, translated from Spanish. The spelling of names and the long cast of characters was confusing, even towards the end. But, the ending was unexpected and a major jackpot payoff. There, I’ve now set lofty expectations for you.

One of the scenes involving a dinner with Aztec priests in attendance was brilliant. Enrigue’s skilled up-close depiction of the shock and confusion of the conquistadors in a completely unrelatable, alien culture was well done.

And here’s the rest of the books, roughly in the order of their reading completion

- Ha Jin – The Banished Immortal: A Life of Li Bai. One of the most important Chinese poets, Li Bai lived in the 8th century, during the Tang Dynasty. Chinese poetry is a topic I’m vaguely interested in but being unable to read the poems in their original language is a major hurdle. Eliot Weinberger’s Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei: How a Chinese Poem is Translated is a short read that presents the problems of translating Chinese poetry and how a single short poem by Wang Wei (Deer Grove) has spawned myriad translations.

- Alice Munro – Selected Stories Volume Two: 1995-2009. I finished volume one in 2024. Munro is Canadian and the winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize for Literature. She belongs to a list of writers (including Ken Liu and Dan Wang) that on a glass-half-empty day incites me with great envy and dissuades me from writing. What’s the point if I would never be able to achieve even half their writing ability. Recently, shocking aspects of Munro’s personal life have been revealed and how much of tragic fact has been embedded in her fiction is being questioned. The main reason why this isn’t in the top 8 list is because I left it out inadvertently.

- Caroline Maniaque-Benton – Whole Earth Field Guide. I bought this alongside several other related books when I was in a Stewart Brand phase. The idea of this book – a selection of recommended reading from Brand’s Last Whole Earth Catalog was appealing but the selection was mostly meh and left me feeling cold. I don’t have the physical copy with me but The Smokey the Bear Sutra is kinda cool.

- Keith Ridgway – A Shock. I read his earlier novel Hawthorn & Child and read this one based on the former’s strengths. This wasn’t as good.

- Hanif Kureishi – The Buddha of Suburbia. I first read this around the same time as One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest about 20 years ago. This time round, I understood most of the cultural references. Did it hold up? There were good bits, there were funny bits, but most of the bits were merely alright. That said, this 1990 novel is an interesting record of how prejudiced views on race and religion have changed for the better (mostly) in the UK.

- Jeff Vandermeer – Absolution. The fourth volume in Vandermeer’s Southern Reach “trilogy”. If you liked the weird fiction of the first three books, you probably would be satisfied with this. If not, then don’t bother.

- Jhumpa Lahiri – Interpreter of Maladies. A more than decent collection of stories mostly about the Indian diaspora in the US and their families. Like Kureishi’s Buddha of Suburbia, relatively groundbreaking for its time but less remarkable in today’s context amid the proliferation of minority/translated fiction available in English.

- Helen DeWitt – The Last Samurai. A book that confuses people every time I recommend it – “Is that the Tom Cruise movie?” Nope, it came out about the same time but is completely unrelated to the movie. It is related however to Akira Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai. A child genius, his single mother, and his quest to find his father. This was still really good but upon rereading it, I felt slightly let down. It wasn’t as amazing as I remembered. That said, her new book Your Name Here is on my to-read list. Here’s a NYT profile of DeWitt and her new book.

- Alex Pheby – Mordew. Sprawling weird fantasy that is intriguing enough for me to want to know what happens next while reading. But not intriguing enough for me to recall the plot.

- Margaret Atwood – The Blind Assasin. Would recommend. Just that my expectations had been raised by all the plaudits and I kind of knew a major spoiler in the plot before reading it.

- Granta 169: China. Volume 169 of this venerable magazine features fiction and non-fiction by Chinese writers. A mixed bag but I finished feeling I had a better cultural understanding of the Chinese people today.

- Ruth Ozeki – A Tale for the Time Being. My first Ozeki. It surpassed my expectations. A pleasurable more-ish, dare I say “comfort” read. No spoilers here.

- Jeremy Cooper – Brian. About a loner who isn’t really lonely, who chances upon the British Film Institute in London’s Southbank, and who finds meaning and companionship at the movies. Fairly niche and possibly infuriating if you’re not a cinephile. But I like movies and I fondly miss the one year I had visiting the BFI.

- Benjamin Moser – The Upside-Down World: Meetings with the Dutch Masters. I started reading this in 2024, in anticipation of my trip to Amsterdam and Rotterdam. I couldn’t finish it in time and only got back to it in the middle of this year. It is a gentle introduction to the Dutch masters and their paintings. Unfortunately, completing this book felt more of a chore as the anticipation of reading about the Dutch masters before seeing their paintings in real life had long expired and it felt like homework. The writer is also the translator of Clarice Lispector whose Hour of the Star I tried reading in 2025 but just couldn’t get into. Maybe this year then.

- Kerry Brown – The Taiwan Story: How a Small Island Will Dictate the Global Future. I wanted to fill gaps in my knowledge about Taiwan – one of the key global flashpoints today. I felt that this book is “too current”, i.e., written in a way that would put it out of date too quickly, which actually means that Brown delivers what is promised in the title. On Taiwan, short of visiting the place (which I haven’t), I would instead recommend Edward Yang’s 1991 movie set in 1960s Taipei – A Brighter Summer Day. You won’t learn about the strategic importance of semiconductors and supply chains but you probably would better understand the history of the place during that era. And that teenage violence isn’t particularly new (not a spoiler, as its literally mentioned in the movie’s original Mandarin title – Youth Homicide Incident on Guling Street).

- Willa Cather – Death Comes for the Archbishop. There has been a mild resurgence of interest in Cather’s writing recently and I’ve seen lots of praise for her work. This was my first time reading her. She portrays the spiritual and cultural colonisation of the Catholic Church in New Mexico and is sympathetic to the lives of both the clergy and the converted. My only other point of reference is John Steinbeck’s The Pearl (which I was forced to read in secondary school). Steinbeck’s novel is one-dimensional compared to this.

- John Krygier and Denis Wood – Making Maps: A Visual Guide to Map Design for GIS (3rd edition). Slightly dated but still a good textbook and reference.

- Jonathan Glassi and Robyn Creswell (editors) – The FSG Poetry Anthology. A selection of poetry published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the past 75 years.

- Jonathan Buckley – One Boat. The second Buckley novel I read, on the strength of his earlier novel Tell. Longlisted for the 2025 Booker Prize. Started strong, ended moderately. Read Tell instead.

- Stephen Dunn – The Not Yet Fallen World: New and Selected Poems. This was a year of splurging on books by poets who wrote one or two poems that I have enjoyed in the past. And then finding out I am not a fan of the rest of their oeuvre.

- Dan Davies – The Unaccountability Machine: Why Big Systems Make Terrible Decisions – and How The World Lost its Mind. I bought this one on the strength of Davies’ Substack. I did learn quite a far bit and could relate to it profesionally. I also enjoyed the author’s dry wit. However, not a book that I would rave and wave in people’s faces.

- Solvej Balle – On the Calculation of Volume I. I knew that it had some Groundhog Day premise. So I held out. Hasn’t that trope been done to death? I was proven wrong. I have recommended it to some people and am looking forward to reading the next few volumes.

- Miranda July – No One Belongs Here More Than You. Just like Kureishi’s Buddha of Suburbia and Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies, this feminist collection of stories full of unlikeable freaky female protagonists would have been revolutionary for its time. Reading it 18 years after it was first published, I would not recommend it unless you were a specific type of reader.

- Jonathan Buckley – Telescope. Of the three Jonathan Buckley novels I read this year, this was the most relatable and “enjoyable”. Was this the best of the three, it wasn’t the worst but the best was Tell, in terms of literary achievement.

- Natsume Soseki – Botchan. Soseki is one of those writers whose writing I think I will enjoy, but never do. This early novel of his isn’t half bad, but it isn’t good. There are several English translations of this. I have two. The one I read is probably the most recent one and has been criticised for being readable but too “American”.

- Jessica Zhan Mei Yu – But the Girl. The premise of this novel would appeal to readers of certain categories. I fall into the intersection of a few of those categories and passed the book on to my friend who intersects with even more of those categories. The plot revolves around the daughter of Malaysian Chinese migrants to Australia. She is writing a PhD thesis on Sylvia Plath alongside a postcolonial novel. And then she goes to the UK for a residency programme.

- Kingsley Amis – The Alteration. Age is catching up with me. I only realised that I had read this novel once, some 15 years ago, as I was nearing the end. An alternate history where the Reformation didn’t happen, King Henry the 8th didn’t “establish” Anglicanism, and Catholicism still reigns in England. Science is negatively perceived, the church rules, the Dutch hold on to the USA as “New England”, there are no black slaves (but there are native American slaves). A fun easter egg is the mention of Philip K Dick’s book “The Man in the High Castle” – Amis admired Dick’s writing.

- Paul Muldoon – Joy in Service on Rue Tagore. One of the biggest names in poetry alive today. Haven’t really read him but enjoyed this poem of his As, despite not fully understanding it. Much of this collection flew over my head. Here are some of the words describing his poetry in his Wikipedia entry – difficult, sly, allusive style, casual use of obscure or archaic words, understated wit, punning, deft technique in meter and slant rhyme, takes some honest-to-God reading, a riddler, enigmatic, distrustful of appearances, generous in allusion, doubtless a dab hand at crossword puzzles. Speaking of crossword puzzles, 2025 was the year I learnt how to properly do NYT crossword puzzles and enjoyed it!

- Ghost Cities – Siang Lu. Came across this from the Guardian, saw it on sale at a secondhand bookstore in Melbourne, grabbed it straight away. My edition has a whole list of Australian awards/nominations this book won on the front cover. Not Ken Liu amazing but very well done. A mix of Chinese history, magical realism, fantasy, and sci fi. Very more-ish. A page turner and recommended. The author is from Malaysia/Singapore I think, and writes screenplays for Astro?

- Quesadillas – Juan Pablo Villalobos. The first half was amazing and was turning out to be a five-star read. There were bits that literally made me laugh out loud. The second half was disappointing – the magical realism twist felt like a cop-out. I’m not a fan of magical realism so maybe you might enjoy this more than me.

- Mathias Énard – Tell Them of Battles, Kings, and Elephants. A short alternate history novel about dreams and ambitions. The artist Michelangelo wants to leave his mark on history by designing a bridge in Constantinople that will make him outshine Leonardo da Vinci. An above average read with outstanding bits.

- Maureen F. McHugh – China Mountain Zhang. I only knew two things about this sci-fi novel before I read it. That it was republished as an SF Masterwork and that it’s set in a future where China and a version of socialism with Chinese characteristics dominates rather than the US and neoliberalism. How topical! This novel formed of loosely connected stories was more gripping and nuanced than I expected. Chanced upon this in that same Melbourne secondhand bookstore mentioned earlier – Seddon Book Alley. One of the best secondhand bookstores, period. Most secondhand bookstores have a low density of quality books. Seddon Book Alley has plenty of curated choicy selections and decent prices.

Online links

Onto some of the most interesting/useful/insightful stuff I read online this year. This list is not comprehensive/representative. I have a longgg backlog of reading links. Also, I only decided to compile this in the last week of December, sifting through links that I shared with friends on WhatsApp throughout the year. I’ve tried to group them into sensible categories, but like most good things, many of them are not easily classifiable and overlap multiple categories.

Curating these took way longer than I expected. What a labour of love.

1. Trying to make sense of yesterday, today, and tomorrow

- Derek Thompson (Dec 2025). The 26 Most Important Ideas for 2026. Self-recommending. Thompson often brings new insights to the table.

- Jonathan Freedland, The Guardian (Dec 2025). The sight of it is still shocking: 46 photos that tell the story of the century so far. Anglo-american-centric but an interesting aide-memoire. I still remember where I was when 9/11 happened. It was the school holidays because I was allowed to use the computer at night in the days of dial-up, chatting with friends on MSN Messenger. The TV was next to me, tuned to NTV7. And then there was a sudden breaking news broadcast.

- Ed Bradon, Works in Progress (Sep 2025). Systems Thinking Isn’t a Magic Bullet. “System thinking promises to give us a toolkit to design complex systems that work from the ground up. It fails because it ignores an important fact: systems fight back.” Perhaps pair this with Donella Meadows 2008 book Thinking in Systems: A primer.

- Afra Wang, Asterisk (Oct 2025). The China Tech Canon. The Silicon Valley Canon is so 2024. Afra’s substack is often a delight too – see, e.g., The Room where AI Happens.

- Tanner Green, The Scholar’s Stage (Sep 2025). Bullets and Ballots: The Legacy of Charlie Kirk. I only knew who Charlie Kirk was after his death. This was a good summary of who he was and why he mattered to a good chunk of American society and beyond.

- Scott Alexander, Astral Codex Ten (Apr 2025). The Colors of Her Coat. Scott Alexander guides us down rabbit holes, intentionally and rationally, so that we can discover even more rabbit holes. Here, he explores medieval art, pigments, OpenAI, and Ghiblification.

- Stephen Abram, Stephen’s Lighthouse (Apr 2014). 25 Fascinating Charts of Negotiation Styles around the World. Hilarious and true. I occasionally remember that this exists and look at it for a laugh. Having encountered different nationalities throughout my professional life, I can vouch for this.

- Gal Beckerman, The Atlantic (Dec 2025). What If Our Ancestors Didn’t Feel Anything Like We Do? cue L,P. Hartley’s quote – “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there”.

- Roger’s Bacon, Secretorum (Apr 2025). The Grand Encyclopedia of Eponymous Laws. I love eponymous laws – they encapsulate wisdom and experience in an entertaining but (mostly) true soundbite. Professionally, I repeatedly witness Parkinson’s Law of Triviality, Sturgeon’s Law, Brooks’ Law, and Goodhart’s Law. On the Internet, I swear that Godwin’s Law and Cunningham’s Law hold true.

- Venkatesh Rao, Contraptions (Jan 2025). The Modernity Machine. “2025 in a 1300 mirror”. Looking backwards to look forwards – the longue longue durée.

- Nicholas Decker, Homo Economicus (May 2025). A Summer Reading List for the Bright and Ambitious Student. I wish I was a bright and ambitious student. This list is still good reading for a less bright and less ambitious student like myself. Lots of chewy papers to sink your teeth into on topics including economic geography, development, and innovation.

- Abraham Thomas, Pivotal (Jan 2025). Making Markets in Time: Silicon Valley and the Invention of Temporal Arbitrage. Does what it says on the tin.

- Brian Albrecht, Vox (Dec 2025). The Only Number that Really Matters – there was once I was convinced that Bhutan was enlightened. That their focus on Gross National Happiness instead of GDP was correct. I swung back in later years. This essay summarises the topic better than I can.

- Davide Pfiffer, PifferPilfer (Nov 2025). The Genetic Evolution of the Human Race and Its Consequences for the Industrial Revolution. Wading into deep and dangerous waters here. Pfiffer investigates a question with dangerous consequences – “was there a measurable genetic trend in traits linked to education and productivity?” He says most likely yes.

- Rohit Krishnan, Strange Loop Canon (Jun 2025). What Happened in the 2010s? The opening sentences ring true: “One reason I love the financial markets is that it’s the best representation about the future, which makes it the perfect tableaux to understand big developments that changed the world. At any scale you look you learn something true about the world.”

- Andrew Batson, The Tangled Woof (Aug 2025). Historical Trajectories of Local Government in India and China. As per Dan Wang, if China is a nation of engineers and the US is a nation of laywers, is India a nation of federal and state level bureaucrats?

- Dan Davies, Back of Mind (Dec 2025). What Is Once Sprung Cannot Necessarily Be Unsprunged. What cognitive hysteresis is and why it matters. Policymakers often ignore this.

2. Diving into data

- Adam Salisbury, Asterisk (Sep 2025). Why Governments Can’t Count. An excellent intro to censuses and the problems of statistics and data in real life. It is very irksome when “experts” sling datapoints as if they were universal truths. More so when they do not know what they are talking about. The last census in India might have missed counting 28 million people while Nigeria, one of the largest and fastest growing countries in the world hasn’t had an official census in 20 years. Find out why this matters.

- Joseph Heath, In Due Course (Jun 2025). Highbrow Climate Misinformation. This is a zinger! On mistaken beliefs on climate change perpetrated and perpetuated not by the general public but by university professors. As Jonathan Swift wrote, “falsehood flies, and the truth comes limping after it.”

- Jo Lawson-Tancred, Artnet (Aug 2025). How Economists Are Mining Art with A.I. to Track Major Social Shifts. A brilliant use of quantitative methods and art history to inform economics! The article has a link to the original paper by Gorin, Heblich, and Zylberberg.

- Daniel Parris, Stat Significant (Feb 2025). How Do Music Listening Habits Change with Age? A Statistical Analysis. I love deep data dives into fun topics. Stat Significant exists to do this, and does it well.

- The Pudding (April 2025). Wine Animals. Whether you’re teetotal or your breath sparks fires, this is so cool – predicting price and quality of wine based on the animal on the label. And a top-tier interactive data viz.

- Yascha Mounk, Persuasion (Mar 2025). The World Happiness Report is a Sham – I cannot shout it any louder from the rooftops – ALWAYS INTERROGATE THE DATA!

3. Cities and citizens

- Patrick Fealey, Esquire (Nov 2024). The Invisible Man. “A firsthand account of homelessness in America”. Real. Moving. There but for the grace of (G)od go I.

- Jeff Fong and Andrew Miller, Urban Proxima (Jan 2025). That Time Google Tried to Build a Neighbourhood. Remember Sidewalk Labs? Here’s a look back at it.

- Ruben Anderson, Strong Towns (Aug 2018). Most Public Engagement is Worse than Worthless. True story. Preach!

- Samuel Hughes, Works in Progress (Sep 2023). Making Architecture Easy. Works in Progress publishes many enlightening essays on cities and urbanism, with a bold POV. This is one good example.

- Chris Arnade, Chris Arnade Walks the World (Jun 2025). How to Build the Perfect City. A former quant who traded the finance bro life to walk around the world and hang out at McDonald’s restaurants in different cities. Check out his podcast interview with Tyler Cowen here too. Pair this with Joanna Pocock’s Greyhound (it’s on my to-read list)?

- Peter Dizikes, MIT News (Jul 2025). Pedestrians Now Walk Faster and Linger Less, Researchers Find. Arianna Salazar-Miranda, Zhuangyang Fan and their co-authors including Carlo Ratti and Edward Glaeser use new methods to answer old questions. The findings hold true but do the reasons given explain it all? I think there’s more to unpack here.

4. Working

- Alexandr Wang, Rational in the Fullness of Time (Dec 2020). Information Compression: Why the wrong thing happens. Before Alexandr Wang became (in)famous as Meta’s Chief AI Officer, the young upstart had a startup, and was Sam Altman’s roommate. Here in his Substack, he drops truths in his posts. And here’s another good post that repeats Thiel’s advice in Zero to One – “Hire People Who Give a Shit” (iykyk).

- Alex Danco, Andreessen Horowitz (Oct 2025). Builders, Solvers and Cynics: The Three-Player Game of Online Tech Sentiment. I confess that my natural instinct is to often revert to being a cynic – the target of this essay. I shall do better.

- Benjamin Todd, 80,000 Hours (Jun 2025). How Not to Lose Your Job to AI. Actionable advice. But will it still hold a year after it’s written?

- Dan Hockenmaier, Dan Hock’s Essays (Sep 2024). How to be Strategic. A good kick in the arse and reminder to self.

- Paul Graham (Jul 2009). Maker’s Schedule, Manager’s Schedule. Paul Graham is one of my GOATs. Reading and rereading Graham is a spiritual journey that reveals wondrous things. This essay articulates what is true to me – the work day is filled with constant interruptions. They could be valid and important. But a “maker” works differently from a “manager” and operates on a different schedule.

- Naval (Nov 2025). Curate People. Are you even taking notes, bruv?

5. Living

- Warren Buffett (Nov 2025). Letter to Shareholders. Warren’s Buffett’s annual letters are full of good investing advice. Much of which is also great life advice. Here’s his final letter.

- Sandra Newman, Aeon (Sep 2015). Man, Weeping. “History is full of sorrowful knights, sobbing monks and weeping lovers – what happened to the noble art of the manly cry?” Fun facts: Jesus wept is the shortest verse in the Bible and also an expletive in some English-speaking parts of the world.

- Cate Hall, Useful Fictions (Jul 2025). Learn to Love the Moat of Low Status. I went back to university in London, nearly 1.5 decades having left it. I thought I didn’t value “status”. Apparently, I did.

- Erik Hoel, The Intrinsic Perspective (Jun 2025). More Lore of the World: Field Notes for a Child’s Codex: Part 2. This essay has intriguing perspectives on the quotidian – “when you become a new parent, you must re-explain the world, and therefore see it afresh yourself”. I quote a comment from one of the reader’s named Mark aka DOPPELKORN: “Awesome writing. Pulitzer-level. Better: ‘best-of-Hoel’-level.”

- Felix Hill, (Dec 2024). On Mental Health, Psychedelics and Life. Hill wrote this in August 2024 and killed himself in December that year. A Google DeepMind scientist’s suicide note with poignant lessons on living.

- Sam Graham-Felsen, New York Times (May 2025). Where Have All My Deep Male Friendships Gone? Is there a male loneliness epidemic? My experience is that the number of close friends I have is dwindling. When I was young (late teens/early 20s) I used to hang out easily, carefree, with friends I grew up with. The future was amorphous and too far away, only the present was real. Many of these friends have moved away; left Malaysia; carried on living separate lives, busy with families, jobs, and the very many commitments life throws at us.

- Henrik Karlsson, Escaping Flatland (Apr 2025). Sometimes the Reason You Can’t Find People You Resonate with is Because You Misread the Ones You Meet. Perhaps an antidote to the issues mentioned in the previous link.

- Jasmine Sun, Jasmine’s Substack (Sep 2025). Are you High-Agency or an NPC? This is filed under “living” and not “working” simply because everything discussed applies to everything one does.

6. Creating

- Celine Nguyen, Personal Canon (Dec 2025). Writing is An Inherently Dignified Human Activity. Nguyen is possibly a contender for one of the best “non-professional” literary reviewers on Substack today.

- Alexander Sorondo, Metropolitan Review (Mar 2025). The Last Contract: William T. Vollmann’s Battle to Publish an American Epic. Vollmann, a modern-day Job gets diagnosed with colon cancer, his daughter dies, his publisher drops him, a car hits him, he gets a pulmonary embolism… He is the quintessential “method writer”, a writer who researches by immersion. He travels to war zones and risks his life. He crossdresses as “Dolores” (despite being an ostensibly heterosexual cis-male). He writes lengthy books and refuses to budge on artistic choices, which result in his publisher of 30 years dropping him. The bright note is that his new 3,400-page brick will be published in the first quarter of 2026.

- The Guardian (Mar 2025). “A Machine-Shaped Hand”: Read a story from OpenAI’s new creative writing model. The future is now. This story was actually really good. Even Jeanette Winterson agrees!

- Anne Boyer, Bookforum (Jul 2015). Not Writing. This is an extract from Anne Boyer’s book “Not Writing”. The prose is hypnotic and reading it is a reminder to be kinder to myself. Here’s a taster:

- “There is illness and injury which has produced a great deal of not writing. There is cynicism, disappointment, political outrage, heartbreak, resentment, and realistic thinking which has produced a great deal of not writing.

- There is the way that the lives of others seem so often unenviable and only enviable as they are “writing” when all this time is spent not writing like right now in the not writing in which I should be dealing with bills, mail, laundry, my bedroom, months of emails from October onward even though it is now June, with my jobs, with care, with the contents of my refrigerator, with my flat tire, with the cat’s litter box, with friendship, with Facebook, with my body which wants to get in the swimming pool with my body which wants to turn brown in the sun with my body which wants to drink some tea with my body which wants to do shoulder presses which wants to join a gym which wants to take a shower and get cleaned up which wants a lover which mostly wants to swim and then there is “not writing.” There is envy which is also mixed with repulsion at those who do not have a long list of not writing to do.”

- Marcin Wichary, Ares Luna (Feb 2018). Japan Design Details. Warning: A VERY deep plunge down a rabbit hole. This is a long compilation of the author’s Tweets on discovering unexpected and enlightened details during his Japan travels. Check out his other post too on his adventures of learning about the Gorton font.

- Ben Davis, Artnet (Mar 2025). Here’s What Makes Caspar David Friedrich’s Edgy Landscapes So Special. Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog is a favourite painting. This essay situates Friedrich’s work within the Weltanschauung of his zeitgeist (hah!) As a corollary, it reminds us of the age-old question of separating art from the artist and judging them by the standards of their time, background, and available privileges (e.g., education and social pedigree).

- Lisa Charlotte Muth, Datawrapper blog (Mar 2022). A Detailed Guide to Colors in Data Vis Style Guides. The Datawrapper blog is a treasure trove for newbies at data visualisation. Even old hands can learn something new. I chanced upon this helpful guide when I was looking for advice on choosing a signature background colour as distinguished as the Financial Times’ salmon pink. I landed on something close to what is called “warp drive” or “aqua squeeze”.

- Joseph Heath, In Due Course (Oct 2023). Why the Culture Wins: An Appreciation of Iain M. Banks. There is an Iain M. Banks gap in my reading. In this essay, Heath contrasts the likes of Dune, Star Wars, and Star Trek against Banks’ underrated Culture series. The Culture explores how tech advancements have far-out consequences on social and political structures and institutions. How au courant.

- The Marginal Revolution Podcast, Mercatus Center (Sep 2025). In Praise of Commercial Culture: Revisiting Tyler’s 1998 Book: What it Got Right, What’s Changed, and Whether Markets Still Make Art Better. Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok of Marginal Revolution fame discuss Tyler’s book. I think its views are still iconoclastic. Excellent.

- Sheon Han, Asterisk (Nov 2025). Reading Lolita in the Barracks: What Does it Take to Turn South Korea’s Mandatory Military Service into a Literary Retreat? Describing this essay as merely the author’s attempt to read while serving in Korea’s National Service is saying that Kesey’s One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest is merely about some people living in a psychiatric ward. Beautifully written. Cruelty and cognitive dissonance are universal and go hand-in-hand. Interesting that the economist Ha-Joon Chang’s book Bad Samaritans is on the military’s list of banned books.

Bonus material

Vibe of the year: John Mayer’s Stop this Train

Craziest shit i binge watched: All episodes of Neon Genesis Evangelion – particularly the last. First time watching it in the year of its 30th anniversary.

Three truths:

It wasn’t that the job was boring. The right kind of boredom can be hypnotic, soothing. It’s that it was utterly ineffectual. Some university bureaucrat had decided to collect data on whether resources were being effectively used, but the figure I was capturing was a bad measure of this, and it would probably never be referred to, and I knew it. I was tasked to be the useless extension of someone else’s uselessness.

Good books are compressed thoughts. They are like seeds: when you plant them in your mind, they explode from their casings and shoot up from the ground—growing much vaster than it feels reasonable a little seed like that could possibly grow. In seven hours, I can read a book of thoughts that someone spent two years thinking. There are few ways of spending seven hours that can compete with that.

Nobody tells people who are beginners — and I really wish somebody had told this to me — is that all of us who do creative work … we get into it because we have good taste. But it’s like there’s a gap, that for the first couple years that you’re making stuff, what you’re making isn’t so good, OK? It’s not that great. It’s really not that great. It’s trying to be good, it has ambition to be good, but it’s not quite that good. But your taste — the thing that got you into the game — your taste is still killer, and your taste is good enough that you can tell that what you’re making is kind of a disappointment to you, you know what I mean?

A lot of people never get past that phase. A lot of people at that point, they quit. And the thing I would just like say to you with all my heart is that most everybody I know who does interesting creative work, they went through a phase of years where they had really good taste and they could tell what they were making wasn’t as good as they wanted it to be — they knew it fell short, it didn’t have the special thing that we wanted it to have.

And the thing I would say to you is everybody goes through that. And for you to go through it, if you’re going through it right now, if you’re just getting out of that phase — you gotta know it’s totally normal.

And the most important possible thing you can do is do a lot of work — do a huge volume of work. Put yourself on a deadline so that every week, or every month, you know you’re going to finish one story. Because it’s only by actually going through a volume of work that you are actually going to catch up and close that gap. And the work you’re making will be as good as your ambitions. It takes a while, it’s gonna take you a while — it’s normal to take a while. And you just have to fight your way through that, okay?

Focus for 2026:

1. Embrace the suck.

2. Hone my craft.

3. Be kinder to myself.

4. Wash my hands more often (to avoid being the useless extension of someone else’s uselessness, iykyk).

5. Tell all the truth but tell it slant.