Image source: Saul Steinberg Foundation.

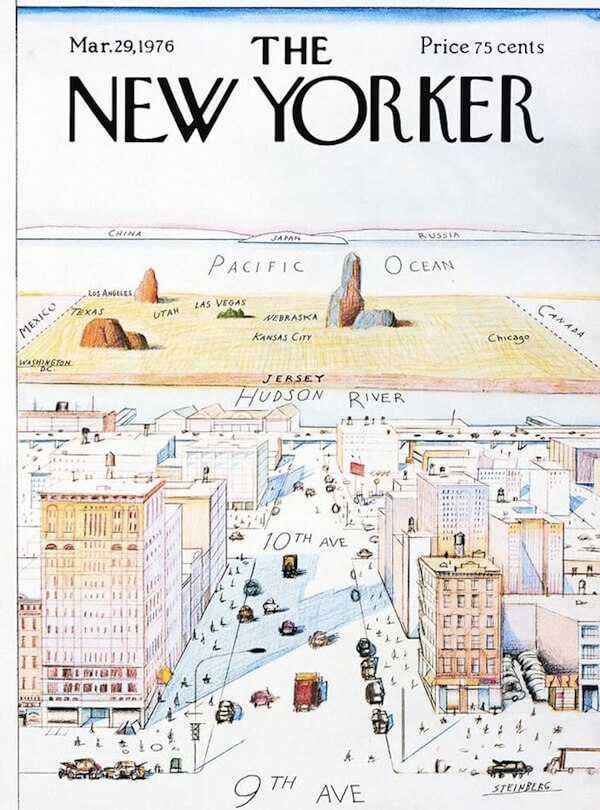

Saul Steinberg’s iconic illustration for the cover of a 1976 issue of The New Yorker depicts a bird’s-eye/drone’s-lens view of New York City from Manhattan Island. Facing west, we see 9th and 10th Avenue lined with rectangle building blocks. We observe far fewer cars parading the streets than today’s typical traffic gridlock. Matchstick people pepper the scene.

Beyond the Hudson River, the rest of the contiguous United States of America is a featureless plain with some rocky outcrops. (New) Jersey is just across the Hudson River. Key cities and states, are labelled with names recognisable to a foreigner: Washington D.C., Kansas City, Chicago, Nebraska, Las Vegas, Utah, Texas, Los Angeles. To the left and right are blank slates labelled Mexico and Canada. Further afield is the Pacific Ocean and beyond, lie three amorphous blobs: China, Japan, Russia.

This image is officially titled “View of the World from 9th Avenue”. Much admired, imitated, and parodied, it is also known by other names including “A New Yorker’s View of the World” and “A Parochial New Yorker’s View of the World”. We get a sense that these unofficial names are a diss at what we imagine the stereotypical New Yorker to be; full of themselves, masters of the universe, who think that the metropolis that they live in — New York City and its surrounding regions is THE city and the centre of the world.

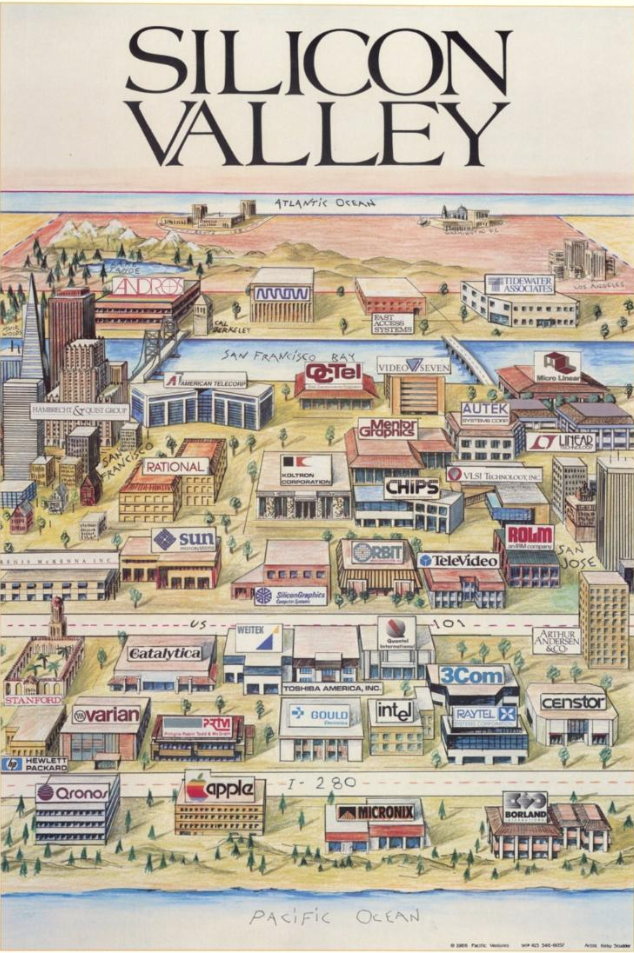

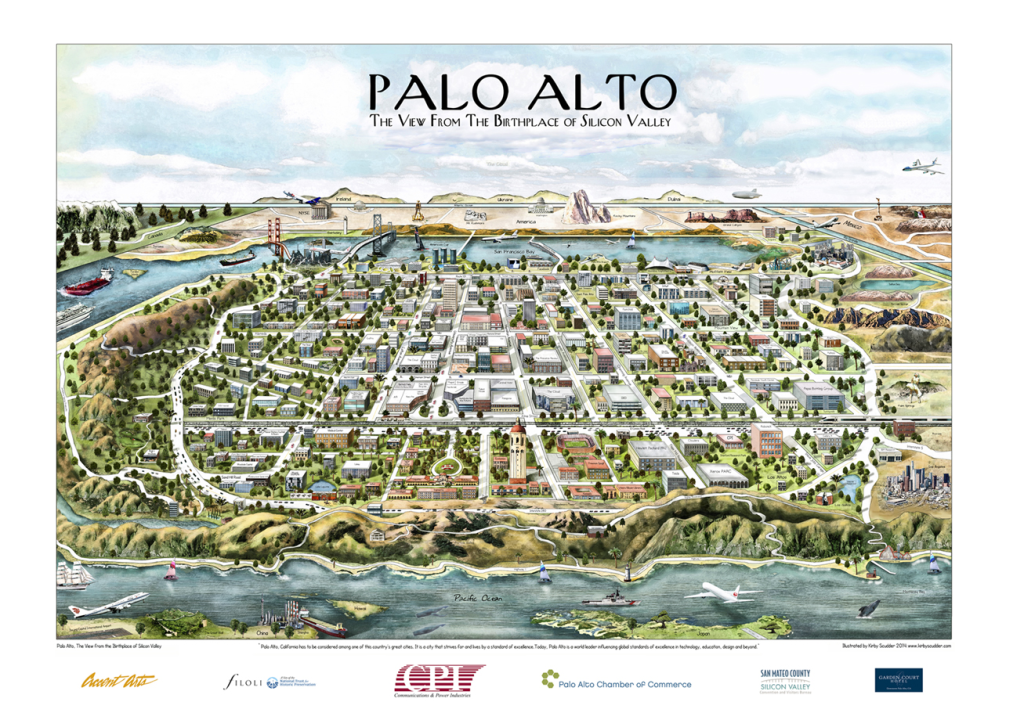

This cover has even been adapted by chambers of commerce globally to promote their cities and organisations. In David Rumsey’s blogpost of “25 Maps of Silicon Valley and Other Tech Hubs”, you can see the influence of Steinberg’s New Yorker cover, particularly Kirby Scudder’s 1986 homage, “Silicon Valley”. Heck, if you visit David Rumsey’s blogpost you can see the influences that led to the industrial map of Malaysia’s own Silicon Island, Penang.

Image source: David Rumsey Historical Map Collection

Image source: Kirby Scudder’s website.

Image source: InvestPenang.

We will revisit the topic of Steinberg’s illustration. For now, we shall explore Christopher Alexander and friends’ first pattern from “A Pattern Language” (see series intro here), I: Independent Regions. I’ve reproduced the headline and solution of this pattern here:

I: INDEPENDENT REGIONS

Headline: “Metropolitan regions will not come to balance until each one is small and autonomous enough to be an independent sphere of culture.”

Solution: “Whenever possible, work toward the evolution of independent regions in the world; each with a population between 2 and 10 million; each with its own natural and geographic boundaries; each with its own economy; each one autonomous and self-governing; each with a seat in a world government, without the intervening power of larger states or countries.”

Alexander et al. (1977) “A Pattern Language”.

Alexander et al. provide four reasons to explain how they have arrived at the conclusion in this headline. Let’s review them one at a time.

First, they state that human government is naturally limited by the size of groups, so independent metropolitan regions need to be a manageable size. They quote the biologist J.B.S. Haldane’s 1956 paper “On Being the Right Size” that just as there is an optimal size for different types of animals, so there is an optimal size for human institutions. Haldane gives the example where in the Greek mode of democracy, all citizens were able to listen to orators and vote directly to pass laws.

Haldane overlooks the fact that citizens partaking in this democracy consisted of less than half the population, with some estimates as low as 10% to 20%. Women, children, slaves, freed slaves, and foreign residents were excluded as they were not “free citizens”. However, we can generally agree with his reasoning about group sizes. Decades later, the British anthropologist Robin Dunbar would come up with his magic number of 150; the number of stable relationships an average human can comfortably maintain.

Alexander et al. delve into network theory to explain why human institutions have a natural size limit. In a population of N persons, an order of N2 person-to-person links are needed to keep information channels flowing smoothly. This calculation is an approximation of Metcalfe’s Law, interestingly proposed by Robert Metcalfe only in 1980, three years after the publication of A Pattern Language.

The larger the size of N, the greater the number of hierarchical levels of government needed for coordination. The authors cite that smaller countries like Denmark have fewer levels. Could this partially explain the success of smaller nations like Singapore? Probably not, if your sample is the countries in the Forum of Small States (population below 10 million, founded by Singapore in 1992). Then again, perhaps if geographically remote small island states were excluded from the sample?

According to Alexander et al., beyond a region’s proposed population range of 2 to 10 million, natural limits are reached. Above this range, people are too far removed from government processes.

However, what is an appropriate definition for a region’s boundaries to determine its population size? What is the appropriate unit of analysis? In the most recent 2020 U.S. census, New York City consisting of the five boroughs had a total population of 8.8 million. Meanwhile, New York City’s metropolitan statistical area (MSA), i.e., the “New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ MSA” had a population of 20 million while its combined statistical area (CSA), i.e., the “New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA CSA” had a population of 22.4 million.

In the Malaysian context, should Kuala Lumpur be considered a distinct unit from Petaling Jaya? What about Klang? Today, Kulim in Kedah, situated at the border with Penang, is at a farther distance from the nearest sizeable Kedah city (Sungai Petani), and is practically a satellite of Bukit Mertajam in Penang.

The second reason the authors provide is that an independent region should be large enough to have a seat at the table of world government, supplanting the power and authority of existing nation-states. They highlight Lord Weymouth’s 1973 letter to the New York Times. Lord Weymouth estimated that in the year 2000, the world would have 10 billion people (the actual number in 2000 was 6.16 billion; Lord Weymouth’s figure was a decent enough guesstimate), and that working backwards, an “ideal regional state” would host a population between 5 to 15 million people, resulting in 1000 regional representatives in the United Nations assembly, truly representing the world’s population.

Would a balanced representation of 1000 regions act as a more effective world government than the present-day United Nations? Perhaps a first step would be to replace the veto powers of the UN Security Council’s permanent members with a more equitable framework.

The third reason given by the authors is that each region needs to be self-governing, otherwise “they will not be able to solve their environmental problems”. I interpret the authors’ use of the word “environmental” in this context as relating to the territory within the region. Indeed, the principle of “subsidiarity”, where issues should be dealt with at the most immediate or local level has been proven to make sense.

However, in the context of “environmental” pertaining to the typical use of the term, today I’m less certain that these environmental problems can best be resolved through mechanisms at the level of these metropolitan region units. Indeed, the Nobel Prize winning economist Elinor Ostrom argued for “A Polycentric Approach for Coping with Climate Change” (which I’ve yet to unpack and digest, so I cannot comment on).

Alexander et al. explain that “the arbitrary lines of states and countries, which often cut across natural regional boundaries, make it all but impossible for people to solve regional problems in a direct and humanly effective way”. Indeed, this brings to mind how colonialists carved up the world along arbitrary lines, particularly in Africa and South Asia. W. H. Auden wrote a poem on the partition of India by Cyril Radcliffe, reproduced here for your reading pleasure.

Partition

W. H. Auden (1966)Unbiased at least he was when he arrived on his mission,

Having never set eyes on this land he was called to partition.“Time,” he was briefed in London, “is short. It’s too late

For compromises, concessions, rational debate;

There isn’t a chance of peace through negotiation:

The only hope now lies in regional segregation.

We cannot help. What with one thing and another,

The Viceroy feels you shouldn’t see much of each other.

Four judges, representing the parties interested,

Will advise, but in you alone is authority invested.”Shut up in an ugly mansion, with police night and day

Patrolling the garden to keep assassins away,

He got down to his job, to settling the political fate

Of millions. The available maps were all out of date,

The census returns almost certainly incorrect,

But there was no time to revise them, no time to inspect

Contested areas himself. It was frightfully hot,

And a bout of dysentery kept him constantly on the trot,

But in seven weeks he had carried out his orders,

Defined, for better or worse, their future borders.The next day he sailed for England, where he quickly forgot

The case as a lawyer must: return he would not,

Afraid, as he told his club, that he might be shot.

Which brings us to the fourth and final reason which I quote here: “unless the present-day great nations have their power greatly decentralized, the beautiful and differentiated languages, cultures, customs, and ways of life of the earth’s people vital to the health of the planet, will vanish. In short, we believe that independent regions are the natural receptacles for language, culture, customs, economy, and laws and that each region should be separate and independent enough to maintain the strength and vigor of its culture”.

Is it fair to accuse Alexander and friends of flirting with autarky? Their views have a tinge of xenophobia, through my lenses today. They believe that “regions of the earth must also keep their distance and their dignity in order to survive as cultures”. The idea that culture thrives when it is isolated is a fallacy. Some of the best cultural creations have emerged and evolved from the collisions and tensions of clashing beliefs and worldviews.

Japanese ukiyo-e woodprint posters influenced Western impressionists and post-impressionists. The transformation of feudal Japan during the Meiji Restoration beginning 1868 was spurred by increased exposure and cross-cultural exchange with western imperialist powers. Similarly, Türkiye was dragged into the modern world by its first president, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1923, amid great warfare with foreign powers. Would an isolated or integrated North Korea and Iran be objectively better for the independent regions of the world today?

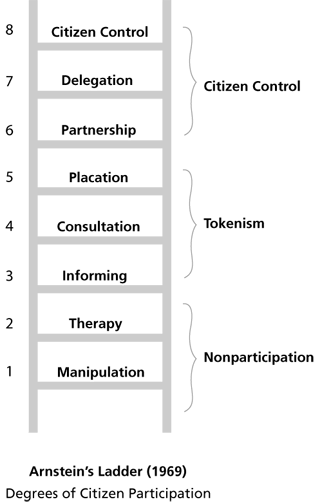

Alexander et al. state that in medieval times cities were “great communes, whose citizens were co-members, each with some say in the city’s destiny”. However, the 2 to 10 million population size they suggest is too large for direct democratic participation. In 1969, Sherry Arnstein introduced “A Ladder of Citizen Participation”. For a region of 2 to 10 million, it is hard to implement and shift from what Arnstein terms as “tokenism” towards “citizen control”.

Regarding Alexander et al.’s exhortation for cultural isolation, I juxtapose relevant ideas from the prodigiously prolific economist Tyler Cowen’s 2002 book, “Creative Destruction: How Globalisation is Changing the World’s Cultures”. Cowen makes the argument that the idea of a cultural “level playing field” is a myth; even ancient Greek city-states never competed culturally on an even basis. Cultural exchange is most productive in dynamic settings in great imbalance rather than when the environment is calm or operating smoothly.

He contrasts “operative diversity” (how effectively we can enjoy all the diversity that is available globally) with “objective diversity” (what amount of diversity actually exists). We lament McDonaldisation and Starbucksification, and curse the cut-and-paste more-of-the-same vibes of hipster cafes around the globe. But Cowen argues that those living in these same-ification regions today have much greater opportunity to pursue different options in their lives and their cultural consumption choices.

He argues that cross-cultural exchange alters and disrupts societies, but simultaneously supports greater innovation and creative energies. And that the cultural ethos is more important than population size since a favourable ethos can help relatively small populations achieve cultural miracles. He cites the example of classical Periclean Athens with a population of less than 200,000 and Renaissance Florence of maximum 80,000 at most times. These societies were open to discovery, new ideas, and acts of creativity and creation. The intellectual and creative output of these societies continue to astound us today.

A successful cultural ethos is scarce, unique, and fragile, according to Cowen. His Minerva Model neatly sums this up: “cross-cultural contact often mobilises the creative fruits of an ethos before disrupting or destroying it.”

We see a common pattern. The initial meeting of cultures produces a creative boom, as individuals trade materials, technologies, and ideas. Often the materially wealthier culture provides financial support for the creations of the poorer culture, while the native aesthetic and ethos remains largely intact. For a while we have the best of both worlds from a cultural point of view. The core of the poorer or smaller culture remains intact, while it benefits from trade. Over time, however, the larger or wealthier culture upsets the balance of forces that ruled in the smaller or poorer culture. The poorer culture begins to direct its outputs towards the tastes of the richer culture. Communication with the outside world makes the prevailing ethos less distinct. The smaller culture “forgets” how to make the high-quality goods it once specialised in, and we observe cultural decline.

I refer to this as the Minerva model. In this scenario a burst of creative flowering also brings the decline of a culture and an ethos. Even when two (or more) cultures do not prove compatible in the long run, they may produce remarkable short-run gains from trade. “Minerva” refers to Hegel’s famous statement that “the owl of Minerva flies only at dusk,” by which he meant that philosophic understanding of a civilisation comes only when that civilisation has already realised its potential and is in decline. I reinterpret the metaphor to refer to cultural brilliance instead, which in this context occurs just when a particular culture is starting its decline. Alternatively, it may be said that cultural blossomings contain the seeds of their own destruction.

Tyler Cowen, “Creative Destruction: How Globalization is Changing the World’s Cultures” (2002)

Independent regions are a crucible for a temporary equilibrium that allow a cultural ethos to flourish. Perhaps there is merit to Alexander et al.’s suggestion that the independent metropolises should be of comparable sizes. Cowen mentions that larger societies like Japan, the US, and Germany are able to absorb external influences and evolve, without losing their identity while smaller societies are at risk of inundation. However, smaller cultures are not complete destroyed, and can regroup and reform with a new synthetic culture.

Cowen discusses lots more interesting ideas including how the Internet allows us to break from the constraints of spatial proximity, liberating ethos from geography; concepts of diversity across not just geography but time; how groups attempt to freeze cultures in specific historical eras (e.g., “Bali as it was in 1968”); and what diversity is desirable, and for whom. All these ideas question our view of culture which influences how we see the world.

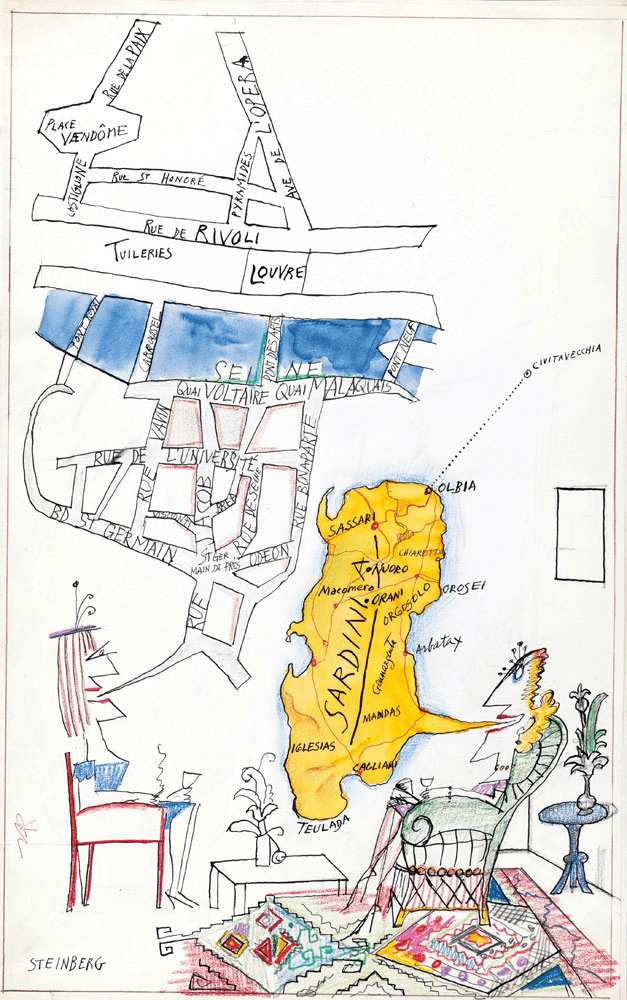

Perhaps a more apt illustration would be of the Île-de-France (Island of France, i.e., Paris) juxtaposed with the Island of Corsica, an Italian-leaning island annexed by France in 1769.

Image source: Saul Steinberg Foundation

Which brings us back to Steinberg’s “View of the World” New Yorker cover. I chanced upon Maria Bustillos’s article in Popula that refers to Deirdre Bair’s biography on Steinberg, revealing what he originally intended in his illustration. Steinberg wasn’t making fun of the smug superiority of supposedly sophisticated New Yorkers. Instead, he was depicting the everyday ordinary “crummy” New Yorkers, the working classes, the hoi polloi, the riffraff, the marginalised, and disenfranchised.

“Steinberg’s ordinary “crummy” New Yorkers are rendered as impersonal rubber stamps who live in the “crummy” parts of town seldom seen by tourists, and who are too busy just making it through another day to have time to think about the larger world beyond the appointed rounds of where they live and work.

After the magazine’s legendary reader, “the little old lady in Dubuque,” enjoyed her moment of condescension with the cover, she and the rest of Steinberg’s viewers wanted to know why none of his typical landmarks were included to identify the grandeur for which the city is famous. He had a ready answer: this was a drawing of how “the crummy people”—that is, the working classes—see the world that lies beyond their immediate neighbourhood. He never intended to make people feel superior or even comfortable when they looked at this drawing, for his thoughts about America, particularly New York and its environs, had darkened considerably during the past decade.

Deirdre Bair, “Saul Steinberg: A Biography” (2012)

Steinberg was depressed by the cheerful optimism of people who went to town with his cover. He was aggravated by the monetisation, imitation and plagiarism. He winced as he passed by souvenir shops selling imitations of his illustration, even managing to successfully sue Columbia Pictures for violating his copyright in the poster for the 1984 movie Moscow on the Hudson, starring Robin Williams.

Image source: Wikipedia.

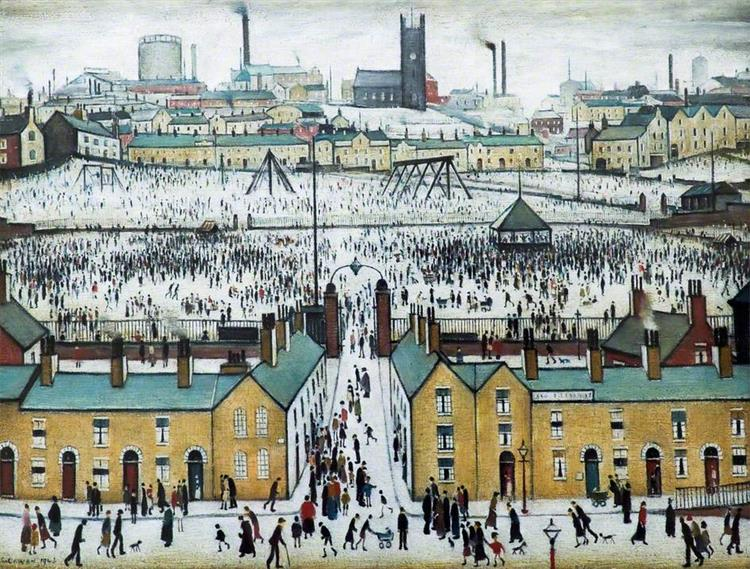

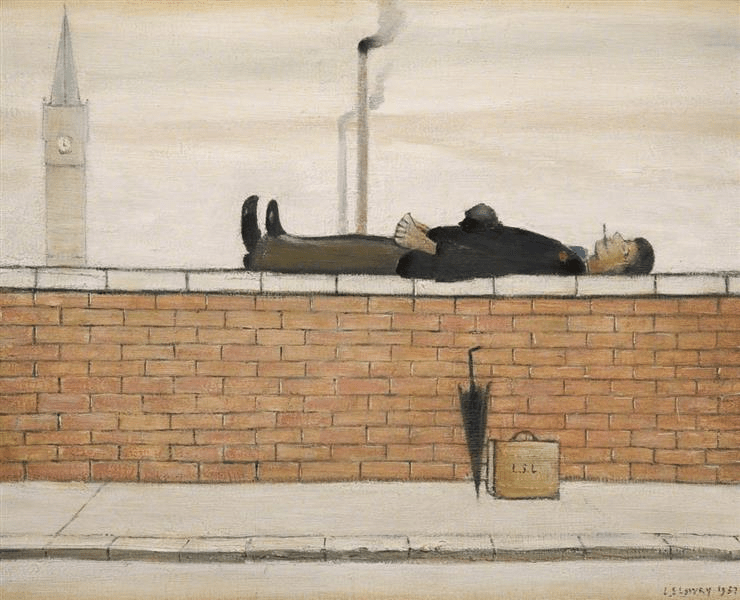

One final digression before the end. Steinberg’s New Yorker cover reminded me of the English artist, L.S. Lowry who was both loved and derided for his “Matchstick Men” paintings, and was unfairly labelled as a naïve “Sunday painter”. Lowry mainly lived and worked in Greater Manchester, itself another industrial and cultural metropolis in its heyday. The Mancunian band Oasis would later feature a Lowry inspired music video for their song “The Masterplan” in 1998.

Two particular works stand out for their similarities to the Steinberg illustration, “Britain at Play” (1943) and “The Canal Bridge” (1949), particularly because of their angle and perspective. I’ve thrown in a bonus painting that I found appealing, “Man Lying on a Wall (1957).

Image source: https://www.wikiart.org/en/l-s-lowry/britain-at-play-1943

Image source: https://www.wikiart.org/en/l-s-lowry/the-canal-bridge-1949

Image source:https://www.wikiart.org/en/l-s-lowry/man-lying-on-a-wall-1957

What can we conclude about Alexander et al.’s first pattern of independent regions? Even in a great metropolis like New York, Steinberg’s “crummy” New Yorkers were too bogged down with the struggles and banality of everyday life, unable to flourish in their “independent sphere of culture”.

How would these independent metropolitan regions work in practice? Some independent regions would lean towards empire building and consolidation, swallowing smaller and weaker regions. Can we realistically check human greed and ambition in these regions? How do we overturn existing hegemonies of the regions of today?

We do not yet have a pathway towards implementing reasonable governance mechanisms that enable 1000 regions of 2 to 10 million people each to work in the real world.