Catholics, so the old chestnut goes, excel in revelling in pain, suffering, and misery. As a good agnostic Catholic, the heightened state of global conflict and tension has me contemplating humanity’s great coping mechanism: cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance, the feeling of unease and mental tension when our beliefs and realities collide, that somehow allows to to keep functioning is a feature, not a bug! It helps us to not fall apart, most of the time.

Can we rejoice in birthdays, weddings, even gender reveal parties while children in Gaza, Kharkiv, Naypyidaw, and Darfur pray to see another sunrise? Should Malaysia cosy up to Putin while condemning Israel in the same breath? Cognitive dissonance or hypocrisy?

Two poems come to mind: W.H. Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts” and Jack Gilbert’s “A Brief for the Defense”.

Musée des Beaux Arts

By W. H. Auden

About suffering they were never wrong,

The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree.

In Brueghel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

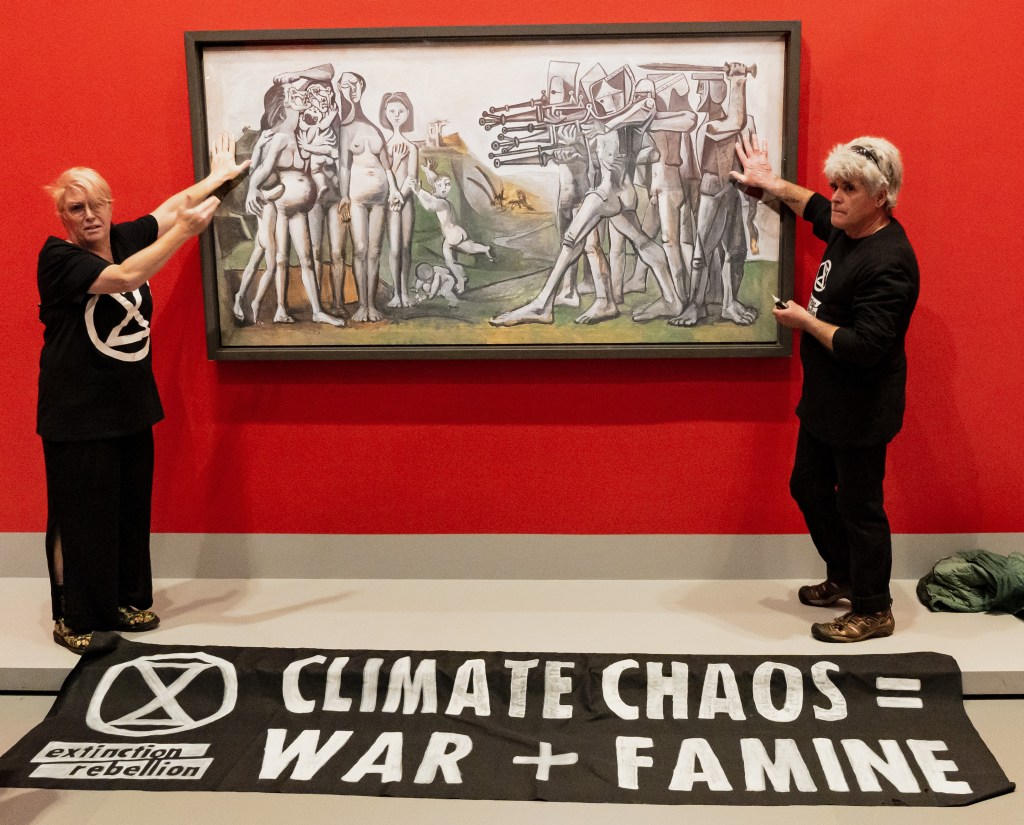

Auden was writing about the painting attributed to Bruegel above, “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus”, in addition to other Bruegel paintings. It’s often forgotten that Icarus flew too close to the sun because he was also avoiding the sea, which would waterlog his wings, making them too heavy. Tragedy takes place to the side, off-stage. We miss the splash and Icarus’ futile air kicks.

While Auden uses “Old Masters” to refer to the painters of the Dutch Golden Age (another contentious term today), a modern-day reader could attribute a second meaning when reading through a post-colonialist lens. Indeed, the Old Masters of Palestine, Ukraine, Myanmar, and Sudan, armed with their imperialist maps are among the key perpetrators of the dire situation today.

In Auden’s poem, whatever happens, the sun will keep shining, the dog will go on with its doggy life, and ships will keep sailing calmly by. We are typically indifferent to the suffering of others. As Bukowski put it, “I guess the only time most people think about injustice is when it happens to them.”

A Brief for the Defense

By Jack Gilbert

Sorrow everywhere. Slaughter everywhere. If babies

are not starving someplace, they are starving

somewhere else. With flies in their nostrils.

But we enjoy our lives because that’s what God wants.

Otherwise the mornings before summer dawn would not

be made so fine. The Bengal tiger would not

be fashioned so miraculously well. The poor women

at the fountain are laughing together between

the suffering they have known and the awfulness

in their future, smiling and laughing while somebody

in the village is very sick. There is laughter

every day in the terrible streets of Calcutta,

and the women laugh in the cages of Bombay.

If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction,

we lessen the importance of their deprivation.

We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure,

but not delight. Not enjoyment. We must have

the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless

furnace of this world. To make injustice the only

measure of our attention is to praise the Devil.

If the locomotive of the Lord runs us down,

we should give thanks that the end had magnitude.

We must admit there will be music despite everything.

We stand at the prow again of a small ship

anchored late at night in the tiny port

looking over to the sleeping island: the waterfront

is three shuttered cafés and one naked light burning.

To hear the faint sound of oars in the silence as a rowboat

comes slowly out and then goes back is truly worth

all the years of sorrow that are to come.

Meanwhile, Gilbert exhorts us to “risk delight. To make “injustice the only measure of our attention” is, he says, “to praise the Devil”. We shouldn’t ignore misery but paradoxically honour it by “enjoy[ing] our lives because that’s what God wants”. Cognitive dissonance or hypocrisy? Each time the splash goes unheard, is that moral courage or convenient self-deception?