Note: This is the first post in a series of layperson reflections on the book, “A Pattern Language”. Each post will focus on one chapter/pattern,

Piet Mondrian’s unfinished, last piece, “Victory Boogie Woogie” and his other similar works were supposedly influenced by the streets and avenues forming the Manhattan city grid. 1 Individual rectangles and squares combine to form ever larger patterns of even more rectangles and squares.

In the urban context, each individual element combines and links with other elements to form a city. A set of buildings and streets form a block. Various blocks form a neighbourhood. Trees and other vegetation make up a park. Vegetation and streets form a green urban corridor.

In Malaysia, we seem to have forgotten that the whole is made up of individual parts. Ensuring individual parts are properly integrated to form a larger urban system would determine if the end result is a harmonious urban orchestra or a cacophony of urban diseconomies of scale. The book “A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction”, published in 1977 gifts us a framework, i.e., “language”, for thinking about these elements. i.e., “patterns”.

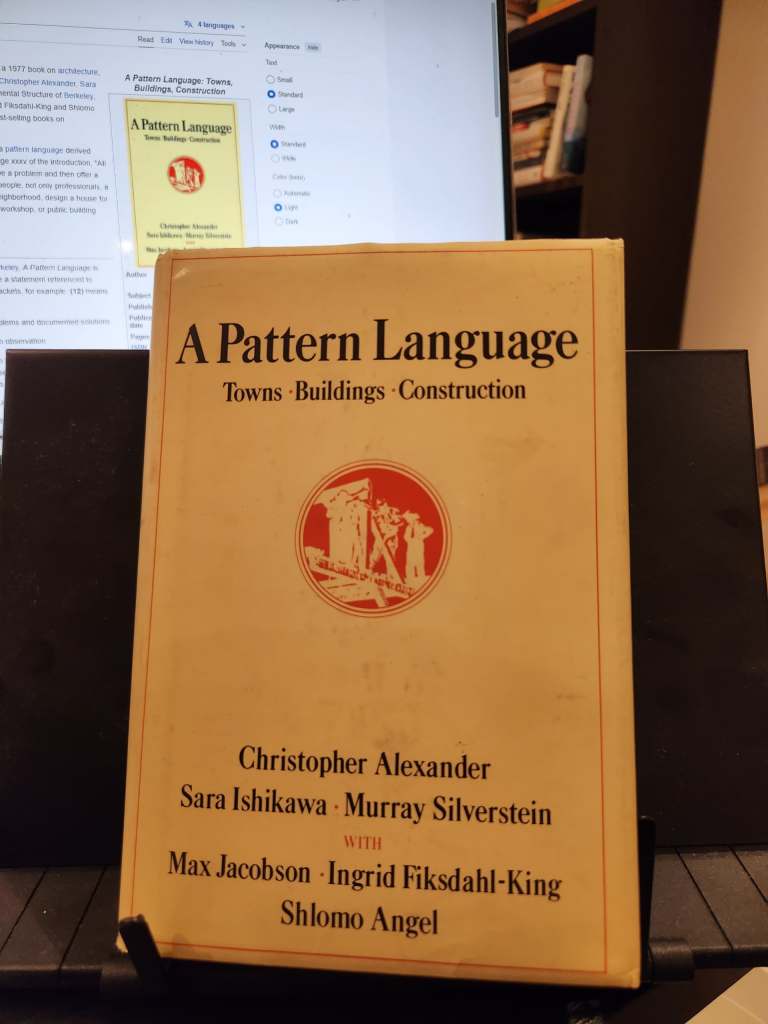

A Pattern Language is synonymous with the British-American architect Christopher Alexander, who was also a professor at the University of California, Berkeley2. However, as you can see in the photo below, the cover lists two other co-authors (Sara Ishikawa, Murray Silverstein) and three other contributors (Max Jacobson, Ingrid Fiksdahl-King, Shlomo Angel). These collaborators are oft forgotten, hence this shout-out to them.3

This book belongs in the Architectural / Urban Planning canon, alongside Jane Jacobs’ “Life and Death of Great American Cities”, Edward Glaeser’s “Triumph of the City”, Stewart Brand’s “How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built”, and Alain Bertaud’s “Order Without Design: How Markets Shape Cities”4. I’ve heard others discuss and reference A Pattern Language for a long time now. Funnily enough, never by Malaysian architects and planners. Among the several architecturally-trained colleagues that I asked, none had heard of the book, while only one had heard of Alexander. Many were aghast at its size (a brick and/or a bible) and its dense paragraphs of text. Someone mentioned to me, “architects don’t read””, something I now believe to be generally true”.5

What is this pattern language? It consists of 253 “patterns” established from the authors’ praxis. These patterns include physical and social patterns and are sequenced from big to small, from the macro region/city/town all the way down to individual construction details. While bigger patterns consist of smaller patterns, the authors state that the language is “in truth a network, there is no one sequence which perfectly captures it”.

The patterns range from the mundane to what might be possibly magical: “1. Independent Regions”, “11. Local Transport Areas”, “32. Shopping Street”, “57. Children in the City”, “75. The Family”, “107. Wings of Light”, “118. Roof Garden”, “204. Secret Place”. For each pattern, the authors provide a problem statement commonly faced, and then offer a solution to that problem.

Interestingly, Alexander and his book have had an outsized influence in computer science and programming, including in the invention of the “wiki” and networks like Wikipedia. A further 80 patterns were introduced in a spiritual sequel: “A New Pattern Language for Growing Regions: Places, Networks, Processes” published in 2020 by a new set of authors and collaborators including Ward Cunningham, inventor of the wiki. The sequel updates the language for the 21st century, ending with these last two patterns: “Augmented Reality Design” and “Citizen Data”. In their introduction, the authors of A New Pattern Language reflect on why the original pattern languages were useful but were unfortunately less influential in the built environment .

“What accounts for the usefulness of pattern languages across such a diversity of fields? They are in essence a way of capturing useful knowledge about the nature of a design problem, and expressing it in a way that can be easily shared and adapted to new contexts. However the form of the knowledge is not rigid, but context-dependent and relational. This feature is especially useful for design problems that require very local and context-specific responses. Of course this is very often the case for problems of urban design, architecture and building too.

What accounts for the comparatively limited development of pattern languages in the built environment – the very field for which they were originally developed? One explanation is that some architects and urban designers do not like what they see as the book’s formulaic design guidance, which they believe constrains their creativity. That may be true for some, but by no means all. Another perhaps more relevant explanation is that, paradoxically, the very success of the 1977 book served to “freeze” the work in a seemingly immutable set of 253 patterns. The book became a best-seller, and an iconic work that some said must not be “tampered with”.

Mehaffy et al. (2020). A New Pattern Language for Growing Regions. pp. 12-13.

Many others have derived their own languages and patterns, notably the urbanist/technologist Drew Austin’s “A Protocol Pattern Language for Urban Space” within the Ethereum Foundation-backed, Summer of Protocols framework. Austin views these patterns through the lenses of “protocols”, i.e., systems with different layers that are “surfaces”6 allowing different individuals or groups who have different levels of agency, to interact with and modify . Austin’s initial “Protocol Pattern Language” includes patterns like “Gig Delivery Break Rooms”, “Neighbourhood Serendipity Protocols”, and “Bureaucratic Recipes”.

“Living in the shadows of global systems and an inflexible built environment, how can individuals reclaim their rightful agency in the places where they live? This document proposes an evolving, open-source toolkit for navigating the spatial and temporal mismatch between these systems and the collective needs of those who use and inhabit them.”

Austin (2023). A Protocol Pattern Language for Urban Space. p. 3.

What would the authors of the original Pattern Language make of these new-fangled patterns native to a world of tech disruption? They would likely welcome these patterns and the disciples who created them with open arms. The original authors were not precious about their pattern language. They state that theirs is just “one possible pattern language” that makes sense to them. Each pattern can be judged individually and modified as needed, without losing the essence that is central to it.

They emphasise that the patterns can be used to “solve the problem for yourself, in your own way, by adapting it to your preferences, and the local conditions at the place where you are making it”.7 Off the top of my head, a Malaysian language could include patterns like the “hawker stall”, “kedai mamak”, “kopitiam”, “wakaf”, “kaki lima”, “gotong royong”, and “open house”.

“… every society which is alive and whole, will have its own unique and distinct pattern language; and further, that every individual in such a society will have a unique language, shared in part, but which as a totality is unique to the mind of the person who has it. In this sense, in a healthy society there will be as many pattern languages as there are people – even though these languages are shared and similar.”

Alexander et al. (1977). A Pattern Language, p. xvi.

The authors also highlight what they call “the poetry of the language”, an act of compressing, overlaying, and/or integrating multiple patterns to create “density”. “Dense” buildings are described as being “profound”. Just like how words in a poem may contain multiple meanings and layers that interlock, multiple patterns can be integrated.

“The compression of patterns into a single space, is not a poetic and exotic thing, kept for special buildings which are works of art. It is the most ordinary economy of space. It is quite possible that all the patterns for a house might, in some form be present, and overlapping, in a simple one-room cabin. The patterns do not need to be strung out, and kept separate. Every building, every room, every garden is better, when all the patterns which it needs are compressed as far as it is possible for them to be. The building will be cheaper; and the meanings in it will be denser.

It is essential then, once you have learned to use the language, that you pay attention to the possibility of compressing the many patterns which you put together, in the smallest possible space. You may think of this process of compressing patterns, as a way to make the cheapest possible building which has the necesary patterns in it. It is, also, the only way of using a pattern language to make buildings which are poems.

Alexander et al. (1977). A Pattern Language, pp. xliii-xliv.

Each pattern is not isolated nor does it exist in a vacuum. This is a fundamental truth that government, professionals, and businesses in the urban domain must not ignore. Patterns are connected to other patterns.

“In short, no pattern is an isolated entity. Each pattern can exist in the world, only to the extent that is supported by other patterns: the larger patterns in which it is embedded, the patterns of the same size that surround it, and the smaller patterns which are embedded in it.

This is a fundamental view of the world. It says that when you build a thing you cannot merely build that thing in isolation, but must also repair the world around it, and within it, so that the larger world at that one place becomes more coherent, and more whole; and the thing which you make takes its place in the web of nature, as you make it.”

Alexander et al. (1977). A Pattern Language, p. xiii.

When you build a thing, you must repair the world around it. We cannot continue doing what we have done in Malaysia, where landowners shortsightedly focus on their respective boundaries and neglect to stitch and connect neighbouring plots in a cohesive manner. This act of neglect is one version of the tragedy of the commons, where the well-being of society is neglected in the pursuit of personal gain.

But I am getting ahead of myself. Let’s dive into the first pattern in the next post.

- In A Pattern Language, the city grid relates to Pattern 15: Neighbourhood Boundary. ↩︎

- In an alternate universe, the owner of this blog completed a Masters in City Planning at this institution. In this universe, he couldn’t get the funding and instead, ended up in London (again) for a year. ↩︎

- Shlomo Angel is still professionally active and based at New York University’s Marron Institute. I’m not sure about the rest. ↩︎

- I intend to discuss these books here. At some point… ↩︎

- So far, I generally believe this to be the norm. ↩︎

- The term “surfaces” here reminds me of “affordances”, in the context of Don Norman’s “The Design of Everyday Things”. I’m still trying to wrap my head around the concept of these Protocols. ↩︎

- Each pattern is also rated with one of three levels of certainty. 2 asterisks (where the authors are certain that the pattern is practically/almost immutably true); 1 asterisk; or no asterisks (where they are certain that they have not succeeded in defining “a true invariant”). ↩︎